✪✪✪✪✪ http://www.theaudiopedia.com ✪✪✪✪✪

What is DEPICTION? What does DEPICTION mean? DEPICTION meaning - DEPICTION pronunciation - DEPICTION definition - DEPICTION explanation - How to pronounce DEPICTION?

Source: Wikipedia.org article, adapted under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ license.

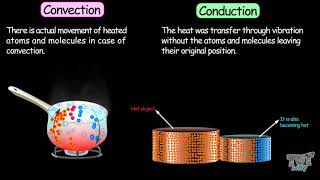

Depiction is a form of non-verbal representation in which two-dimensional images (pictures) are regarded as viable substitutes for things seen, remembered or imagined. Basically, a picture maps an object to a two-dimensional scheme or picture plane. Pictures are made with various materials and techniques, such as painting, drawing, or prints (including photography and movies) mosaics, tapestries, stained glass, and collages of unusual and disparate elements. Occasionally pictures may occur in simple inkblots, accidental stains, peculiar clouds or a glimpse of the moon, but these are special cases. Sculpture and performances are sometimes said to depict but this arises where depiction is taken to include all reference that is not linguistic or notational. The bulk of research in depiction however deals only in pictures. While sculpture and performance clearly represent or refer, they do not strictly picture their objects.

Pictures may be factual or fictional, literal or metaphorical, realistic or idealised and in various combination. Idealised depiction is also termed schematic or stylised and extends to icons, diagrams and maps. Classes or styles of picture may abstract their objects by degrees, conversely, establish degrees of the concrete (usually called, a little confusingly, figuration or figurative, since the ‘figurative’ is then often quite literal). Stylisation can lead to the fully abstract picture, where reference is only to conditions for a picture plane – a severe exercise in self-reference and ultimately a sub-set of pattern.

But just how pictures function (i.e. how they can be viably substituted for three-dimensional objects etc.) is disputed. Philosophers, art historians and critics, perceptual psychologists and other researchers in the arts and social sciences have contributed to the debate and many of the most influential contributions have been interdisciplinary. Some key positions are briefly surveyed below.

Traditionally, depiction is distinguished from denotative meaning by the presence of a mimetic element or resemblance. A picture resembles its object in a way a word or sound does not. Resemblance is no guarantee of depiction, obviously. Two pens may resemble one another but do not therefore depict each other. To say a picture resembles its object especially is only to say that its object is that which it especially resembles; which strictly begins with the picture itself. Indeed, since everything resembles something in some way, mere resemblance as a distinguishing trait is trivial. Moreover, depiction is no guarantee of resemblance to an object. A picture of a dragon does not resemble an actual dragon. So resemblance is not enough.

Theories have tried either to set further conditions to the kind of resemblance necessary, or sought ways in which a notational system might allow such resemblance. The problem is resemblance is a two-way or symmetrical relation between parties; each equally resembles the other, while reference is one-way or asymmetrical, only one points to the other. Converting or combining them would seem to invite a fatal compromise.

In art history, the history of actual attempts to achieve resemblance in depictions is usually covered under the terms "realism", naturalism", or "illusionism".

The most famous and elaborate case for resemblance modified by reference, is made by art historian Ernst Gombrich. Resemblance in pictures is taken to involve illusion. Instincts in visual perception are said to be triggered or alerted by pictures, even when we are rarely deceived. The eye supposedly cannot resist finding resemblances that accord with illusion. Resemblance is thus narrowed to something like the seeds of illusion. Against the one-way relation of reference Gombrich argues for a weaker or labile relation, inherited from substitution. Pictures are thus both more primitive and powerful than stricter reference.

But whether a picture can deceive a little while it represents as much seems gravely compromised. Claims for innate dispositions in sight are also contested. Gombrich appeals to an array of psychological research from James J. Gibson, R. L. Gregory, John M. Kennedy, Konrad Lorenz, Ulric Neisser and others in arguing for an ‘optical’ basis to perspective, in particular (see also perspective (graphical). Subsequent cross-cultural studies in depictive competence and related studies in child-development and vision impairment are inconclusive at best.

Gombrich’s convictions have important implications for his popular history of art, for treatment and priorities there.

dictionaryenglish dictionaryonline dictionary